When Models Manipulate Manifolds: The Geometry of a Counting Task

Abstract

Large language models can perform visual text processing tasks through geometric transformations and attention mechanisms that map token characteristics onto manifolds representing spatial relationships.

Language models can perceive visual properties of text despite receiving only sequences of tokens-we mechanistically investigate how Claude 3.5 Haiku accomplishes one such task: linebreaking in fixed-width text. We find that character counts are represented on low-dimensional curved manifolds discretized by sparse feature families, analogous to biological place cells. Accurate predictions emerge from a sequence of geometric transformations: token lengths are accumulated into character count manifolds, attention heads twist these manifolds to estimate distance to the line boundary, and the decision to break the line is enabled by arranging estimates orthogonally to create a linear decision boundary. We validate our findings through causal interventions and discover visual illusions--character sequences that hijack the counting mechanism. Our work demonstrates the rich sensory processing of early layers, the intricacy of attention algorithms, and the importance of combining feature-based and geometric views of interpretability.

Community

This paper investigates how Claude 3.5 Haiku performs linebreaking in fixed-width text—predicting when to insert newlines based on implicit character-width constraints. The key finding is that the model represents scalar quantities (character counts) on low-dimensional curved manifolds and manipulates them through geometric transformations to perform computation.

1. The Task and Feature Representations

The model must count characters since the last newline and compare this to the inferred line width to determine if the next word fits. The authors find that character counts are represented by families of sparse features analogous to biological place cells—discrete features that tile a continuous manifold (Figure 5).

Figure 5: A family of features representing the current character count in a line. Features exhibit dilation (wider receptive fields for larger counts), similar to biological number perception.

These features discretize a 1-dimensional feature manifold embedded in a low-dimensional subspace (6D). When projected into PCA space, the character count vectors form a twisting helix-like curve where position along the curve corresponds to character count (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Character count is represented on a curved manifold in a 6D subspace. Crosses indicate feature decoder directions; the jagged line shows the manifold parameterized by count.

2. Boundary Detection via Manifold Twisting

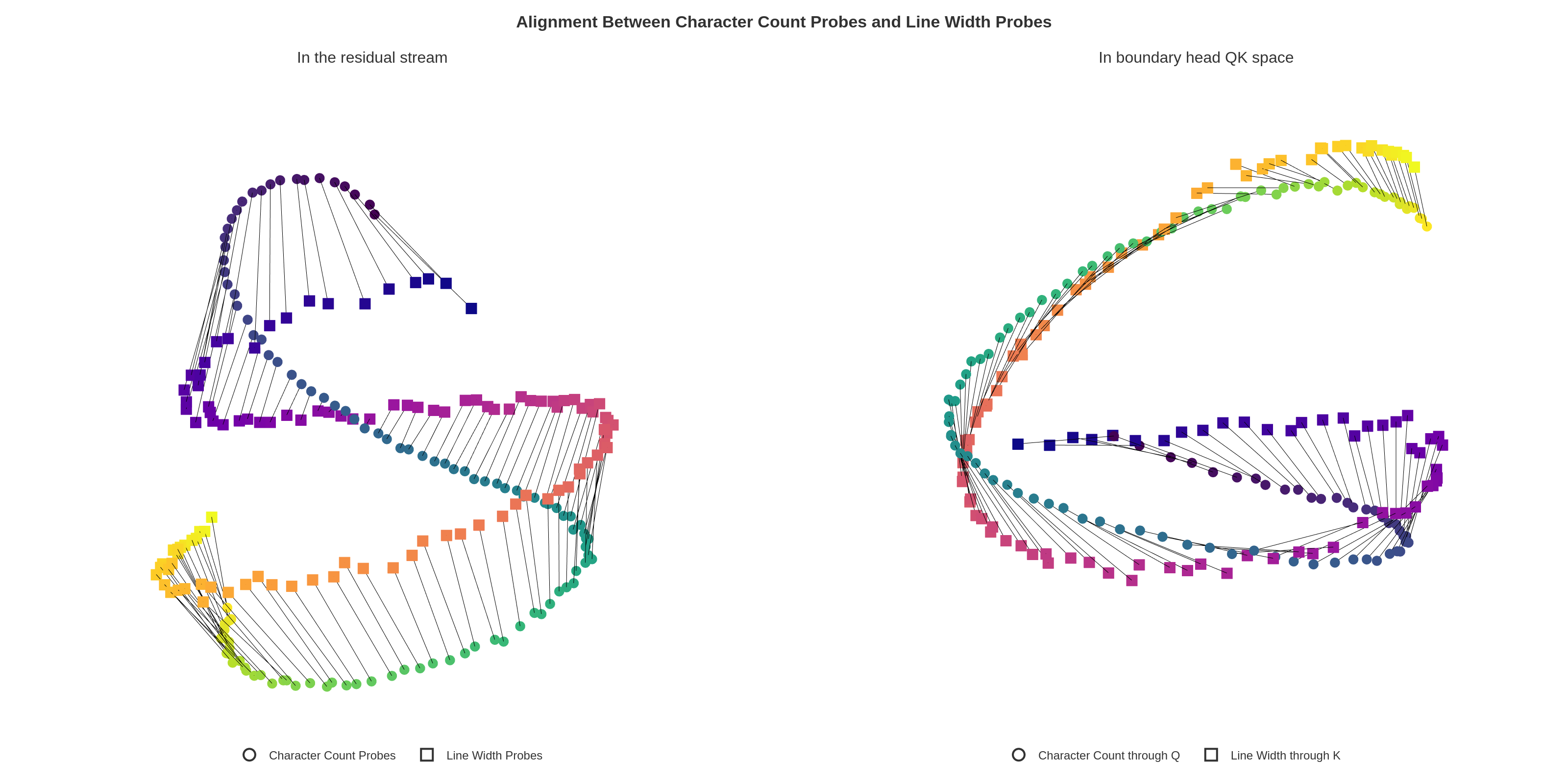

To detect approaching line boundaries, the model compares the current character count with the line width. This is accomplished by attention heads that "twist" the manifolds using their QK matrices:

- Character count manifold and line width manifold begin roughly orthogonal in the residual stream

- Boundary heads rotate the character count manifold to align with line width at a specific offset (Figure 14)

- This creates high inner product when the difference between counts falls within a target range, indicating proximity to the boundary

Figure 14: Left: Joint PCA of character count and line width probes in residual stream. Right: After passing through the QK matrix of a boundary head, the manifolds are twisted to align character count $i$ with line width $k=i+\epsilon$.

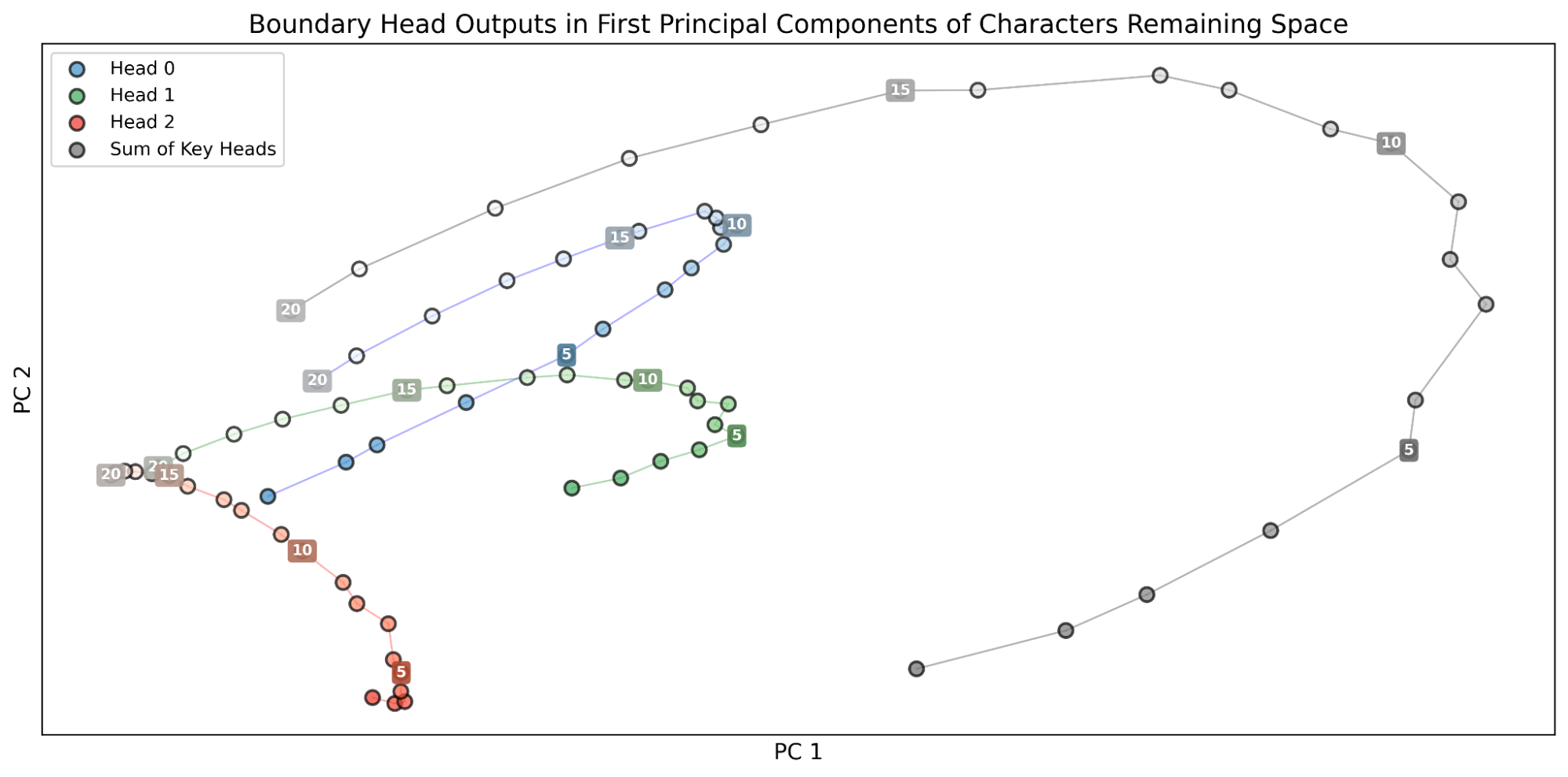

Multiple boundary heads implement a "stereoscopic" algorithm with different offsets, each peaking at different distances from the end of the line (Figure 17). Their outputs sum to provide precise estimation of "characters remaining" across the full range (Figure 18).

Figure 18: Each head's output (left) varies most significantly in different ranges; their sum (right) produces an evenly spaced representation covering all values of characters remaining.

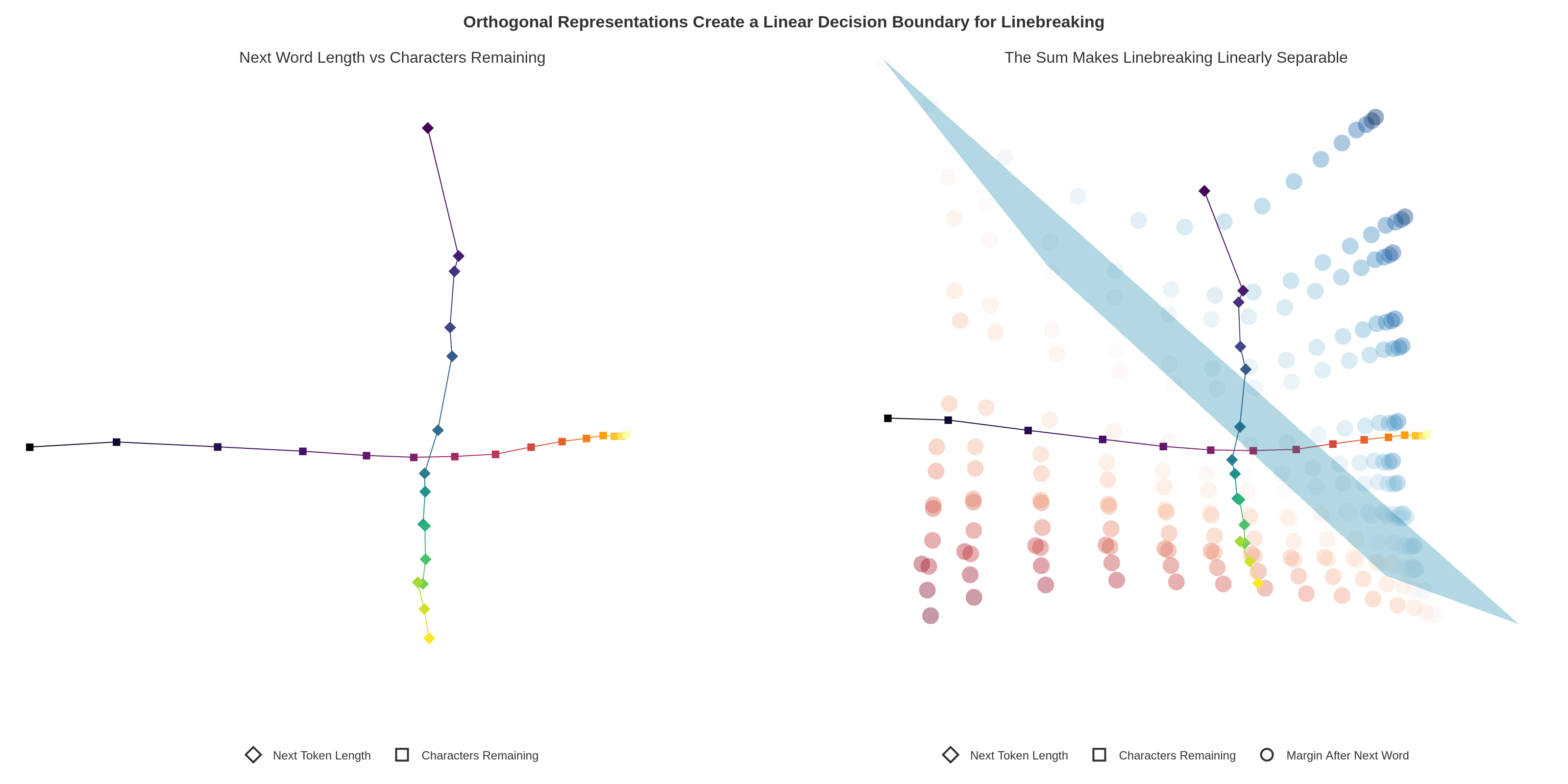

3. The Newline Decision: Orthogonal Geometry

The final decision combines characters remaining with the length of the next predicted word. The model positions these representations on near-orthogonal subspaces, making the decision boundary linearly separable (Figure 23).

Figure 23: Left: PCA showing orthogonal arrangement of "characters remaining" (blue) and "next token length" (red) manifolds. Right: Pairwise sums of these vectors show that the condition "characters remaining $\geq$ next token length" (break line) is linearly separable.

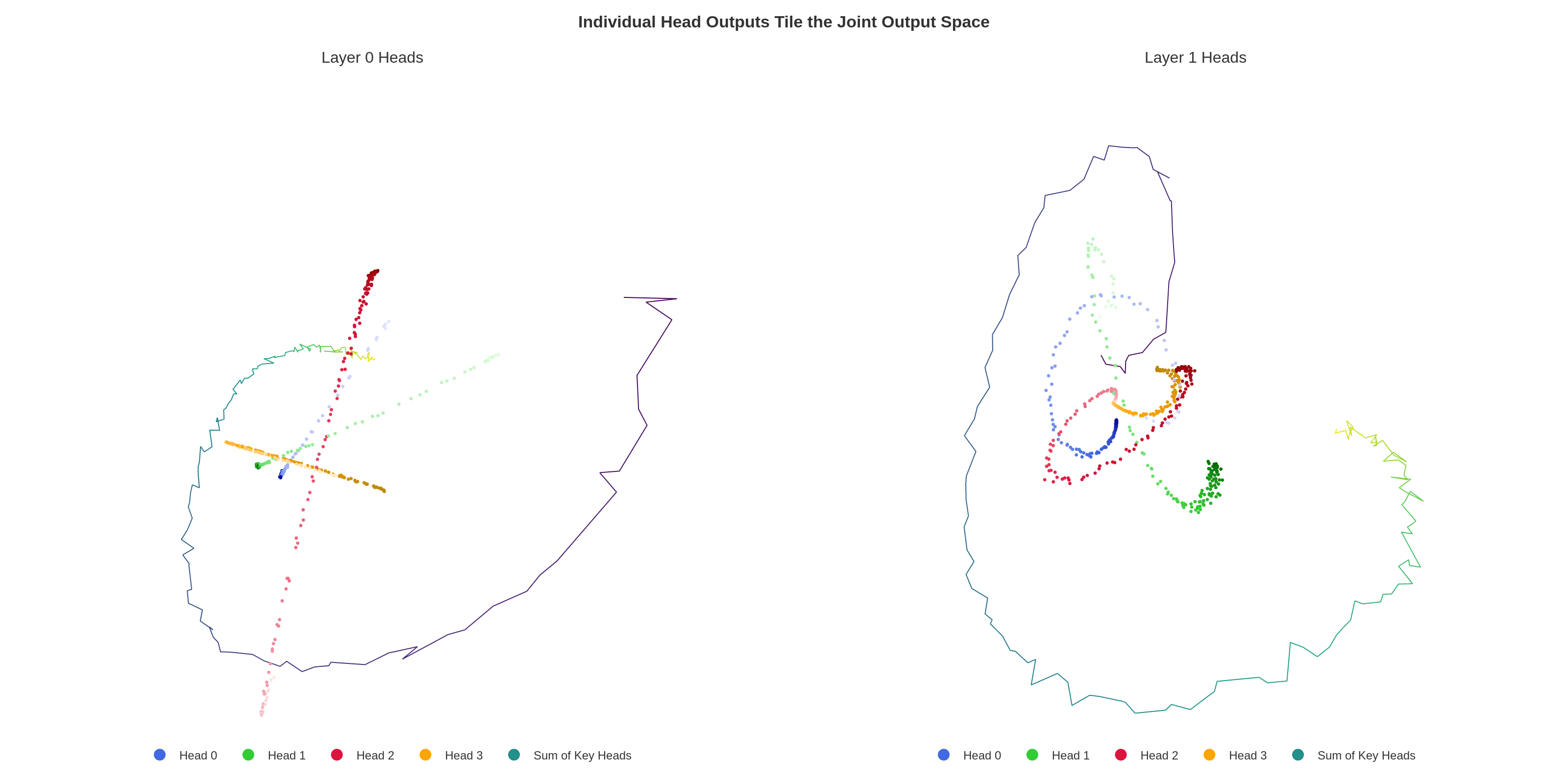

4. Distributed Construction of the Manifold

The curved character count manifold is constructed distributed across multiple attention heads in early layers:

- Layer 0 heads each output rays (1D contributions) at different offsets

- These sum to create the curved manifold in higher layers (Figure 24)

- Individual heads use the previous newline as an "attention sink" and apply corrections based on token lengths

Figure 24: Layer 0 head outputs (left) are nearly 1-dimensional rays; Layer 1 heads (right) display more curvature, sharpening the count estimate.

5. Visual Illusions

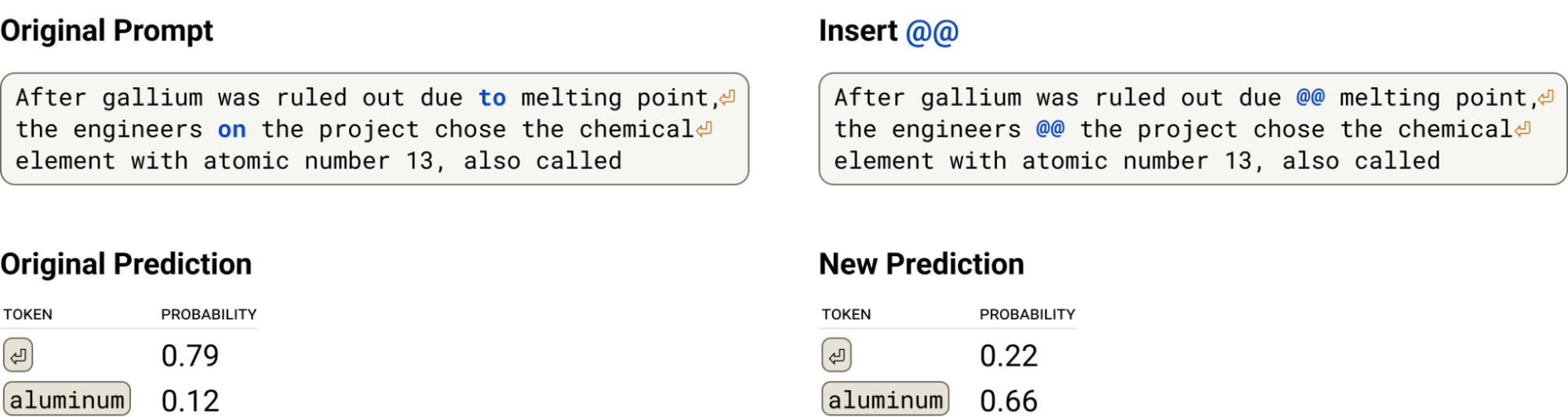

The authors validate the mechanism by constructing adversarial character sequences that hijack attention heads. For example, inserting @@ (a git diff delimiter) distracts counting heads that normally attend from newline-to-newline, causing them to attend to the @@ instead. This disrupts the character count estimate and breaks newline prediction (Figures 31–33), analogous to human visual illusions like Müller-Lyer.

Figure 31: Inserting @@ into the prompt (right) disrupts the newline prediction compared to the original (left), creating a "visual illusion" for the model.

Summary

The paper demonstrates that language models perform sensory processing (counting characters) using rippled, low-dimensional manifolds rather than simple linear encodings. Computation occurs through geometric transformations: twisting manifolds to compare values (boundary detection) and arranging them orthogonally to create linear decision boundaries. This geometric perspective complements traditional feature-based interpretations, revealing how distributed attention heads cooperatively construct and manipulate curved representations to solve spatial reasoning tasks in text.

Models citing this paper 0

No model linking this paper

Datasets citing this paper 0

No dataset linking this paper

Spaces citing this paper 0

No Space linking this paper

Collections including this paper 0

No Collection including this paper